Η κιτικολίνη δεν είναι ακριβώς ένα οικιακό όνομα. Σε αντίθεση με τη βιταμίνη D ή τα ωμέγα-3, οι περισσότεροι άνθρωποι δεν την έχουν ακούσει ποτέ. Αλλά στον κόσμο των συμπληρωμάτων για την υγεία του εγκεφάλου, έχει αναπτύξει μια ήσυχη φήμη μεταξύ των ερευνητών και των συντακτών που γνωρίζουν τη βιβλιογραφία.

Το ενδιαφέρον με την κιτικολίνη είναι το πώς βρίσκεται σε αυτό το παράξενο ενδιάμεσο έδαφος. Δεν είναι αρκετά μοντέρνα για να δημιουργήσει τον θόρυβο που περιβάλλει ενώσεις όπως η χαίτη του λιονταριού ή τα νοοτροπικά κοκτέιλ. Δεν έχει πίσω της τη μηχανή μάρκετινγκ που ωθεί ορισμένα συμπληρώματα στην καθιερωμένη ευαισθητοποίηση. Αλλά δεν είναι επίσης κάποια σκοτεινή ερευνητική χημική ουσία που συζητούν μόνο οι biohackers σε φόρουμ.

Αντίθετα, η κιτικολίνη καταλαμβάνει αυτό το περίεργο χώρο όπου οι άνθρωποι που γνωρίζουν γι' αυτήν τείνουν να την παίρνουν στα σοβαρά, ενώ το ευρύ κοινό παραμένει εντελώς ανυποψίαστο για την ύπαρξή της. Ακόμη και στους κύκλους των συμπληρωμάτων, θα βρείτε ανθρώπους που ορκίζονται σε αυτήν και άλλους που δεν έχουν μπει ποτέ στον κόπο να την εξετάσουν.

Έτσι αποφάσισα να το καταλάβω σωστά. Αυτό που ανακάλυψα ήταν πιο ενδιαφέρον από ό,τι περίμενα - μια ένωση με πραγματική ερευνητική υποστήριξη, κάποιες πρακτικές εφαρμογές και μερικούς σημαντικούς περιορισμούς που σπάνια συζητούνται.

Η κιτικολίνη έχει ένα από εκείνα τα χημικά ονόματα που κάνουν τα μάτια σας να γυαλίζουν: κυτιδίνη 5′-διφωσφοχολίνη. Ευτυχώς, μπορούμε να παραμείνουμε στην κιτικολίνη ή στην άλλη κοινή της ονομασία, CDP-χολίνη.

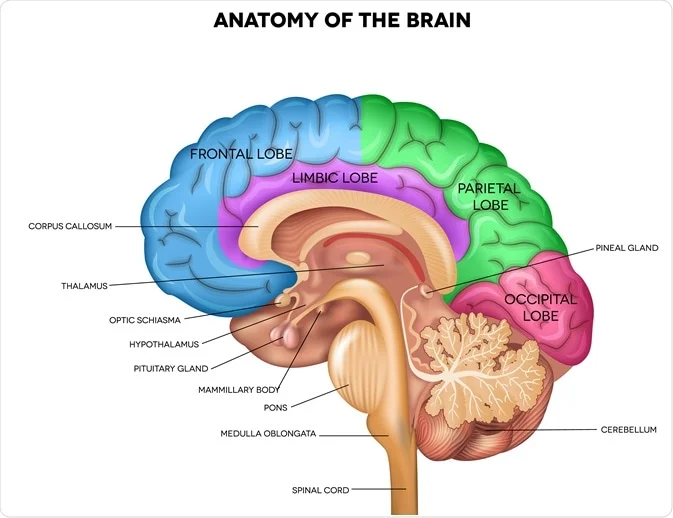

Στον πυρήνα της, η κιτικολίνη είναι μια ένωση που ο εγκέφαλός σας χρησιμοποιεί για να χτίσει και να διατηρήσει τις κυτταρικές μεμβράνες. Σκεφτείτε την ως πρώτη ύλη για την κατασκευή και την επισκευή των εγκεφαλικών κυττάρων. Όταν παίρνετε κιτικολίνη, το σώμα σας τη διασπά σε δύο βασικά συστατικά: χολίνη και κυτιδίνη. Και τα δύο αυτά παίζουν σημαντικό ρόλο στη λειτουργία του εγκεφάλου.

Η χολίνη είναι μάλλον πιο γνωστή - είναι η ίδια ουσία που βρίσκεται στα αυγά και χρησιμοποιείται για την παραγωγή ακετυλοχολίνης, ενός νευροδιαβιβαστή που εμπλέκεται στη μνήμη και τη μάθηση. Το συστατικό κυτιδίνη είναι λιγότερο γνωστό αλλά εξίσου σημαντικό. Βοηθά στη δημιουργία των φωσφολιπιδίων που σχηματίζουν τις μεμβράνες των εγκεφαλικών κυττάρων και υποστηρίζει την παραγωγή νουκλεοτιδίων που χρειάζονται τα κύτταρα για την ενέργεια και την επισκευή.

Αυτή η διπλή δράση είναι που κάνει την κιτικολίνη ενδιαφέρουσα για τους ερευνητές. Τα περισσότερα συμπληρώματα χολίνης παρέχουν μόνο χολίνη. Η κιτικολίνη παρέχει τόσο τη χολίνη όσο και τα δομικά στοιχεία που απαιτούνται για την αποτελεσματική χρήση της στον εγκέφαλο.

Η ένωση εμφανίζεται φυσικά σε κάθε κύτταρο του σώματός σας, αλλά σε πολύ μικρές ποσότητες. Ο εγκέφαλός σας μπορεί να παράγει από μόνος του λίγη κιτικολίνη, αλλά όχι απαραίτητα αρκετή για να καλύψει τις αυξημένες απαιτήσεις κατά τη διάρκεια του στρες, της γήρανσης ή του τραυματισμού. Αυτός είναι ο λόγος για τον οποίο ενδιαφέρθηκαν οι εταιρείες συμπληρωμάτων - η ιδέα είναι ότι η παροχή επιπλέον κιτικολίνης θα μπορούσε να υποστηρίξει τη λειτουργία του εγκεφάλου όταν η φυσική παραγωγή δεν συμβαδίζει.

Υπάρχει όμως ένα σημαντικό κενό μεταξύ αυτής της βιολογικής λογικής και του αποδεδειγμένου θεραπευτικού οφέλους. Η κατανόηση του τι κάνει η κιτικολίνη στο σώμα δεν μας λέει αυτόματα αν η συμπλήρωσή της βοηθάει πραγματικά σε κάτι. Σε αυτό το σημείο έρχεται η έρευνα.

Η κιτικολίνη δεν ανακαλύφθηκε από εταιρείες συμπληρωμάτων που αναζητούσαν το επόμενο ενισχυτικό για τον εγκέφαλο. Προέκυψε από σοβαρές ιατρικές έρευνες στις δεκαετίες του 1970 και 80, όταν οι επιστήμονες προσπαθούσαν να κατανοήσουν πώς τα εγκεφαλικά κύτταρα αποκαθίστανται μετά από τραυματισμό.

Η ένωση συντέθηκε για πρώτη φορά και μελετήθηκε από ερευνητές που ερευνούσαν την αποκατάσταση του εγκεφαλικού επεισοδίου. Ήξεραν ότι οι μεμβράνες των εγκεφαλικών κυττάρων καταστρέφονται κατά τη διάρκεια εγκεφαλικών επεισοδίων και αναζητούσαν τρόπους για να υποστηρίξουν τη διαδικασία επιδιόρθωσης. Η κιτικολίνη τράβηξε την προσοχή τους επειδή φαινόταν να παρέχει τα ακριβή δομικά στοιχεία που χρειάζονταν τα κατεστραμμένα εγκεφαλικά κύτταρα για να ξαναχτίσουν τις μεμβράνες τους.

Οι πρώτες ιατρικές εφαρμογές επικεντρώθηκαν αποκλειστικά σε νευρολογικά επείγοντα περιστατικά - εγκεφαλικά επεισόδια, τραυματικές εγκεφαλικές βλάβες και άλλες οξείες εγκεφαλικές βλάβες όπου τα κύτταρα πέθαιναν ενεργά ή είχαν υποστεί βλάβη. Τα νοσοκομεία στην Ευρώπη και την Ασία άρχισαν να χρησιμοποιούν την κιτικολίνη ως μέρος των τυποποιημένων πρωτοκόλλων θεραπείας για αυτές τις καταστάσεις. Δεν θεωρήθηκε συμπλήρωμα ή ένωση βελτίωσης- ήταν φάρμακο για σοβαρά τραυματισμένους εγκεφάλους.

Η μετάβαση στη γενική υγεία του εγκεφάλου έγινε σταδιακά. Καθώς οι ερευνητές μελετούσαν τις επιδράσεις της κιτικολίνης στους κατεστραμμένους εγκεφάλους, άρχισαν να αναρωτιούνται αν θα μπορούσε επίσης να υποστηρίξει την υγιή λειτουργία του εγκεφάλου. Θα μπορούσε να βοηθήσει με τη γνωστική παρακμή που σχετίζεται με την ηλικία; Τι γίνεται με τη γενική μνήμη ή την εστίαση σε υγιείς ανθρώπους;

Αυτή η μετατόπιση από την επείγουσα ιατρική στην προληπτική συμπλήρωση αντιπροσωπεύει ένα τεράστιο άλμα στην εφαρμογή. Το γεγονός ότι κάτι βοηθά στην αποκατάσταση εγκεφαλικού ιστού που έχει υποστεί σοβαρή βλάβη δεν σημαίνει αυτόματα ότι θα ενισχύσει τη φυσιολογική λειτουργία του εγκεφάλου. Αλλά η βιομηχανία συμπληρωμάτων ενδιαφέρθηκε για αυτή τη δυνατότητα και οι ερευνητές ήταν αρκετά περίεργοι ώστε να αρχίσουν να το δοκιμάζουν.

Εδώ είναι που η ιστορία περιπλέκεται - και εδώ είναι που πρέπει να δούμε τι βρήκαν οι πραγματικές μελέτες.

Η έρευνα σχετικά με την κιτικολίνη είναι πιο εκτεταμένη από ό,τι οι περισσότεροι άνθρωποι συνειδητοποιούν. Τις τελευταίες δύο δεκαετίες, οι επιστήμονες την έχουν δοκιμάσει σε χιλιάδες συμμετέχοντες σε πολλαπλές καταστάσεις - ανάρρωση από εγκεφαλικό επεισόδιο, τραυματική εγκεφαλική βλάβη, γνωστική έκπτωση λόγω ηλικίας και υγιή γήρανση. Το εύρος είναι πραγματικά εντυπωσιακό, καθώς εκτείνεται από μικρές πιλοτικές μελέτες έως μαζικές διεθνείς δοκιμές που περιλαμβάνουν σχεδόν 2.300 συμμετέχοντες σε μεμονωμένες μελέτες.

Τι ανακάλυψαν όμως στην πραγματικότητα; Τα ευρήματα δίνουν την εικόνα μιας ένωσης με γνήσια θεραπευτικά αποτελέσματα, ιδίως στην αποκατάσταση του εγκεφάλου και στη γνωστική υποστήριξη που σχετίζεται με την ηλικία.

Από όλες τις μελέτες κιτικολίνης που διεξήχθησαν κατά τη διάρκεια δύο δεκαετιών, μόνο δύο σχεδιάστηκαν ρητά με πρωταρχικό στόχο την ασφάλεια. Αυτό είναι αξιοσημείωτο αν αναλογιστείτε τις χιλιάδες των ανθρώπων που έχουν μελετηθεί. Η πρώτη ειδική μελέτη ασφάλειας διεξήχθη από τους Hall et al. (2020), μια 12μηνη ανοικτή δοκιμή σε 10 ασθενείς με FXTAS, μια σπάνια νευρολογική πάθηση, χρησιμοποιώντας 1000 mg ημερησίως με εντατική παρακολούθηση, συμπεριλαμβανομένων εργαστηριακών εξετάσεων και ολοκληρωμένης παρακολούθησης ανεπιθύμητων ενεργειών. Η δεύτερη διεξήχθη από τους Secades et al. (2006), μια διπλά τυφλή, τυχαιοποιημένη, ελεγχόμενη με εικονικό φάρμακο πιλοτική μελέτη που εξέτασε την ασφάλεια σε ασθενείς με ενδοεγκεφαλική αιμορραγία σε δόση 1000 mg δύο φορές ημερησίως για δύο εβδομάδες, όπου το πρωτεύον καταληκτικό σημείο ήταν συγκεκριμένα ο αριθμός των ανεπιθύμητων ενεργειών.

Σκεφτείτε το για μια στιγμή. Δεκαετίες ερευνών, χιλιάδες συμμετέχοντες και μόνο δύο μελέτες που έθεσαν την ασφάλεια στο επίκεντρο. Αυτό δεν είναι απαραίτητα πρόβλημα, αλλά μας λέει κάτι σημαντικό για το πώς λειτουργεί συνήθως η φαρμακευτική έρευνα - η ασφάλεια αξιολογείται ως δευτερεύον ζήτημα, ενώ οι ερευνητές κυνηγούν τα αποτελέσματα της αποτελεσματικότητας.

Το πρωτοποριακό έργο προήλθε από την έρευνα για τα εγκεφαλικά επεισόδια, όπου οι επιστήμονες αναζητούσαν απεγνωσμένα οτιδήποτε θα μπορούσε να βοηθήσει τους ασθενείς να ανακτήσουν την εγκεφαλική τους λειτουργία. Οι Clark et al. διεξήγαγαν τις θεμελιώδεις συστηματικές μελέτες δόσης-απόκρισης, ξεκινώντας με τη μελέτη τους το 1997 στο περιοδικό Neurology(Clark et al., 1997), η οποία εξέτασε μεθοδικά διαφορετικές δόσεις σε 259 ασθενείς σε 21 αμερικανικά κέντρα.

Τα αποτελέσματα ήταν εντυπωσιακά. Οι ασθενείς που έλαβαν κιτικολίνη παρουσίασαν σημαντικά καλύτερη γνωστική αποκατάσταση σε σύγκριση με τις ομάδες εικονικού φαρμάκου. Στη βέλτιστη δόση των 2000 mg ημερησίως, οι ασθενείς με εγκεφαλικό επεισόδιο επέδειξαν μετρήσιμα βελτιωμένες βαθμολογίες νευρολογικών λειτουργιών και ταχύτερη αποκατάσταση της γλώσσας, της μνήμης και των κινητικών δεξιοτήτων. Οι βελτιώσεις δεν ήταν ανεπαίσθητες - ήταν κλινικά σημαντικές διαφορές που μεταφράστηκαν σε καλύτερη λειτουργία στον πραγματικό κόσμο.

Ακολούθησε η μελέτη του Clark et al. για το εγκεφαλικό επεισόδιο του 1999 σε 394 ασθενείς, η οποία διαπίστωσε και πάλι ότι "η συχνότητα και το είδος των παρενεργειών ήταν παρόμοια μεταξύ των ομάδων" κατά τη σύγκριση της κιτικολίνης με το εικονικό φάρμακο. Στη συνέχεια, οι ερευνητές ανέβηκαν στη μεγαλύτερη μελέτη τους(Clark et al., 2001), μια δοκιμή φάσης ΙΙΙ σε 899 ασθενείς που δοκίμαζαν 2000 mg ημερησίως, όπου ανέφεραν και πάλι ότι "η συχνότητα εμφάνισης και το είδος των παρενεργειών ήταν παρόμοια μεταξύ των ομάδων".

Αυτή η μαζική μελέτη διαπίστωσε ότι οι ασθενείς που έλαβαν θεραπεία με κιτικολίνη παρουσίασαν ανώτερη ανάκαμψη σε πολλαπλούς γνωστικούς τομείς -προσοχή, σχηματισμό μνήμης και εκτελεστική λειτουργία- σε σύγκριση με την καθιερωμένη φροντίδα και μόνο. Οι βελτιώσεις διατηρήθηκαν κατά τη διάρκεια της περιόδου μελέτης των 12 εβδομάδων και συσχετίστηκαν με καλύτερες βαθμολογίες λειτουργικής ανεξαρτησίας.

Το πληρέστερο σύνολο δεδομένων προέρχεται από τη μαζική δοκιμή ICTUS που διεξήχθη από τους Dávalos et al. (2012), στην οποία συμμετείχαν 2.298 ασθενείς με εγκεφαλικό επεισόδιο σε πολλές χώρες, δοκιμάζοντας 2000 mg ημερησίως. Ενώ αυτή η μελέτη δεν πέτυχε το πρωταρχικό της τελικό σημείο, δηλαδή τη μείωση της συνολικής αναπηρίας, τα γνωστικά αποτελέσματα έλεγαν μια διαφορετική ιστορία. Οι ασθενείς που έλαβαν κιτικολίνη παρουσίασαν σημαντικά καλύτερες επιδόσεις σε τεστ μνήμης, εργασίες προσοχής και μετρήσεις ταχύτητας επεξεργασίας. Τα γνωστικά οφέλη ήταν πιο έντονα σε ασθενείς με μέτριας βαρύτητας εγκεφαλικό επεισόδιο, γεγονός που υποδηλώνει ότι η κιτικολίνη λειτουργεί καλύτερα όταν ο εγκεφαλικός ιστός έχει υποστεί βλάβη αλλά δεν έχει καταστραφεί εντελώς.

Τα αποτελέσματα ήταν εντυπωσιακά ως προς τη συνέπειά τους. Σε όλα τα επίπεδα δόσεων και τους πληθυσμούς της μελέτης, τα ποσοστά ανεπιθύμητων συμβάντων ήταν στατιστικά αδιάφορα από τις ομάδες του εικονικού φαρμάκου.

Καθώς η εμπιστοσύνη στις επιδράσεις της κιτικολίνης αυξανόταν, οι ερευνητές άρχισαν να τη δοκιμάζουν σε πιο υγιείς πληθυσμούς. Εδώ είναι που η ιστορία γίνεται ιδιαίτερα ενδιαφέρουσα για τους χρήστες συμπληρωμάτων.

Μια ιδιαίτερα αποκαλυπτική μελέτη των Nakazaki et al. (2021) εξέτασε 100 υγιείς ηλικιωμένους συμμετέχοντες (ηλικίας 50-85 ετών) επί 12 εβδομάδες, χρησιμοποιώντας 500 mg ημερησίως. Τα αποτελέσματα έδειξαν μετρήσιμες βελτιώσεις σε διάφορους γνωστικούς τομείς που έχουν σημασία για την καθημερινή ζωή.

Οι συμμετέχοντες που έπαιρναν κιτικολίνη επέδειξαν αυξημένη διάρκεια προσοχής - μπορούσαν να επικεντρωθούν σε εργασίες για μεγαλύτερο χρονικό διάστημα χωρίς πνευματική κόπωση. Ο σχηματισμός μνήμης βελτιώθηκε, ιδίως για νέες πληροφορίες και συσχετίσεις προσώπων και ονομάτων. Το πιο σημαντικό, η ταχύτητα επεξεργασίας αυξήθηκε, πράγμα που σημαίνει ότι οι συμμετέχοντες μπορούσαν να σκεφτούν προβλήματα και να λάβουν αποφάσεις πιο γρήγορα από την ομάδα του εικονικού φαρμάκου.

Οι ερευνητές χρησιμοποίησαν ολοκληρωμένες συστοιχίες γνωστικών δοκιμών και όχι μόνο υποκειμενικά ερωτηματολόγια. Μελέτες απεικόνισης του εγκεφάλου σε υποσύνολα συμμετεχόντων έδειξαν αυξημένη δραστηριότητα σε περιοχές που σχετίζονται με την προσοχή και τη μνήμη, γεγονός που υποδηλώνει ότι οι γνωστικές βελτιώσεις είχαν γνήσια νευρολογική υπόσταση.

Τα ευρήματα αυτά ευθυγραμμίζονται με προηγούμενη έρευνα των Spiers et al. (2010) σε υγιείς γυναίκες μέσης ηλικίας, οι οποίες έδειξαν βελτιωμένη προσοχή και ψυχοκινητική ταχύτητα μετά από μόλις 28 ημέρες χορήγησης συμπληρώματος κιτικολίνης σε δόση 250-500 mg ημερησίως.

Η δοκιμή COBRIT(Zafonte et al., 2012) εξέτασε την κιτικολίνη σε 1.213 ασθενείς με περίπλοκη ήπια, μέτρια και σοβαρή TBI σε δόση 2000 mg ημερησίως για 90 ημέρες.

Ενώ το πρωταρχικό λειτουργικό αποτέλεσμα της μελέτης δεν έφτασε σε στατιστική σημαντικότητα, τα γνωστικά αποτελέσματα ήταν συναρπαστικά. Οι ασθενείς με μέτρια τραυματική εγκεφαλική βλάβη παρουσίασαν σημαντικά βελτιωμένη παγίωση της μνήμης, καλύτερο έλεγχο της προσοχής και ταχύτερη επεξεργασία πληροφοριών σε σύγκριση με το εικονικό φάρμακο. Τα αποτελέσματα ήταν πιο έντονα στους ασθενείς που ξεκίνησαν τη θεραπεία εντός 24 ωρών από τον τραυματισμό, γεγονός που υποδηλώνει ότι η κιτικολίνη λειτουργεί καλύτερα όταν οι διαδικασίες επιδιόρθωσης του εγκεφάλου είναι πιο ενεργές.

Ίσως το πιο σημαντικό, αυτές οι γνωστικές βελτιώσεις μεταφράστηκαν σε καλύτερη ποιότητα ζωής και αυξημένη ικανότητα επιστροφής στην εργασία ή το σχολείο - αποτελέσματα που έχουν σημασία πέρα από τα αποτελέσματα των εξετάσεων.

Η έρευνα επεκτάθηκε ακόμη και στην εξάρτηση από ουσίες, όπου οι Yoon et al. (2010) εξέτασαν την κιτικολίνη σε ασθενείς εξαρτώμενους από τη μεθαμφεταμίνη σε δόση 2000 mg ημερησίως. Πέρα από τα ευρήματα για την ασφάλεια, η μελέτη αυτή αποκάλυψε κάτι συναρπαστικό σχετικά με τις ευρύτερες επιδράσεις της κιτικολίνης στη λειτουργία του εγκεφάλου.

Οι ασθενείς που έλαβαν κιτικολίνη παρουσίασαν βελτιωμένο έλεγχο των παρορμήσεων, καλύτερη λήψη αποφάσεων υπό συνθήκες στρες και ενισχυμένη μνήμη εργασίας - γνωστικές λειτουργίες που συνήθως μειώνονται στον εθισμό. Η απεικόνιση του εγκεφάλου έδειξε αυξημένη δραστηριότητα σε προμετωπιαίες περιοχές που σχετίζονται με τον εκτελεστικό έλεγχο. Παρόλο που αυτή δεν ήταν μια μελέτη γνωστικής ενίσχυσης αυτή καθαυτή, κατέδειξε την ικανότητα της κιτικολίνης να υποστηρίζει εγκεφαλικές λειτουργίες ανώτερης τάξης ακόμη και σε πληθυσμούς που βρίσκονται σε κίνδυνο.

Αυτό που κάνει αυτά τα ερευνητικά ευρήματα ιδιαίτερα συναρπαστικά είναι ότι ευθυγραμμίζονται με τους γνωστούς μηχανισμούς της κιτικολίνης. Η ένωση αυξάνει τη σύνθεση φωσφατιδυλοχολίνης στις κυτταρικές μεμβράνες του εγκεφάλου, ενισχύει την παραγωγή ακετυλοχολίνης και υποστηρίζει τον κυτταρικό ενεργειακό μεταβολισμό μέσω της βελτιωμένης σύνθεσης νουκλεοτιδίων.

Μελέτες απεικόνισης του εγκεφάλου δείχνουν σταθερά ότι το συμπλήρωμα κιτικολίνης αυξάνει τη δραστηριότητα σε περιοχές που σχετίζονται με την προσοχή, τη μνήμη και την εκτελεστική λειτουργία. Αυτό δεν είναι απλώς συσχέτιση - οι νευρολογικές αλλαγές ταιριάζουν με τις γνωστικές βελτιώσεις που παρατηρούνται στις δοκιμές συμπεριφοράς.

Να τι μου τράβηξε την προσοχή όταν έψαξα τις μελέτες: παρ' όλες αυτές τις έρευνες, υπάρχει μια αξιοσημείωτη συνέπεια στα ευρήματα ασφαλείας που αποκαλύπτει κάτι σημαντικό σχετικά με το θεραπευτικό παράθυρο της κιτικολίνης.

Από όλες τις μελέτες κιτικολίνης που διεξήχθησαν κατά τη διάρκεια δύο δεκαετιών, μόνο δύο σχεδιάστηκαν ρητά με πρωταρχικό στόχο την ασφάλεια. Η πρώτη ειδική μελέτη ασφάλειας διεξήχθη από τους Hall et al. (2020), μια 12μηνη ανοικτή δοκιμή σε 10 ασθενείς με FXTAS με χρήση 1000 mg ημερησίως με εντατική παρακολούθηση. Η δεύτερη έγινε από τους Secades και συν. (2006), εξετάζοντας την ασφάλεια σε ασθενείς με ενδοεγκεφαλική αιμορραγία σε δόση 1000 mg δύο φορές ημερησίως.

Τα περισσότερα δεδομένα για την ασφάλεια προέρχονται από δοκιμές αποτελεσματικότητας, αλλά οι μελέτες αυτές ήταν εκπληκτικά αυστηρές όσον αφορά την παρακολούθηση της ασφάλειας. Οι πρώιμες μελέτες Clark διαπίστωσαν "καμία σοβαρή ανεπιθύμητη ενέργεια ή θάνατο που να σχετίζεται με το φάρμακο" και κατέληξαν στο συμπέρασμα ότι "η από του στόματος κιτικολίνη μπορεί να χρησιμοποιηθεί με ασφάλεια και με ελάχιστες παρενέργειες". Η μαζική μελέτη ICTUS, στην οποία συμμετείχαν 2.298 άτομα, διαπίστωσε ποσοστά ανεπιθύμητων συμβάντων στατιστικά αδιάφορα από τις ομάδες εικονικού φαρμάκου.

Πέρα από τις ελεγχόμενες δοκιμές, υπάρχουν μαζικά δεδομένα παρακολούθησης από τον πραγματικό κόσμο από τους Cho & Kim (2009 ) που παρακολούθησαν 4.191 ασθενείς που λάμβαναν κιτικολίνη σε δόσεις που κυμαίνονταν από 500 έως 4000 mg ημερησίως. Αυτά τα δεδομένα πραγματικού κόσμου επιβεβαίωσαν το προφίλ ασφάλειας που παρατηρήθηκε στις ελεγχόμενες δοκιμές.

Η συνέπεια της ασφάλειας επεκτείνεται σε πολύ διαφορετικούς πληθυσμούς - ασθενείς με εγκεφαλικό επεισόδιο, υγιείς ηλικιωμένοι ενήλικες, ασθενείς με εγκεφαλική βλάβη και εξαρτημένα από ουσίες άτομα, όλα εμφανίζουν σχεδόν πανομοιότυπα προφίλ ασφάλειας. Αυτή η διαπολιτισμική συνέπεια είναι ασυνήθιστη στην έρευνα για τα συμπληρώματα και υποδηλώνει ένα πραγματικά ισχυρό περιθώριο ασφαλείας.

Η ερευνητική εικόνα που προκύπτει είναι αξιοσημείωτα συνεπής: η κιτικολίνη παρέχει μετρήσιμα γνωστικά οφέλη σε διάφορους πληθυσμούς, με πιο έντονες επιδράσεις στην προσοχή, το σχηματισμό μνήμης και την ταχύτητα επεξεργασίας. Τα οφέλη εμφανίζονται τόσο σε κατεστραμμένους εγκεφάλους που αναρρώνουν από τραυματισμό όσο και σε υγιείς εγκεφάλους που αντιμετωπίζουν την ηλικιακή παρακμή.

Η σχέση δόσης-απόκρισης είναι σαφής από την έρευνα. Οι επιδράσεις γίνονται εμφανείς στα 500 mg ημερησίως σε υγιείς ενήλικες, ενώ τα βέλτιστα οφέλη παρατηρούνται συνήθως στα 1000-2000 mg ημερησίως. Οι γνωστικές βελτιώσεις αναπτύσσονται σε διάστημα εβδομάδων και όχι ωρών, γεγονός που υποδηλώνει ότι η κιτικολίνη λειτουργεί υποστηρίζοντας την υποκείμενη δομή και λειτουργία του εγκεφάλου και όχι παρέχοντας οξεία διέγερση.

Αυτό που κάνει τη κιτικολίνη μοναδική στο χώρο των νοοτροπικών είναι αυτός ο συνδυασμός ισχυρών δεδομένων αποτελεσματικότητας με ένα εξαιρετικό προφίλ ασφάλειας. Τα περισσότερα συμπληρώματα εγκεφάλου είτε στερούνται στέρεων ερευνών αποτελεσματικότητας είτε παρουσιάζουν κενά ασφαλείας. Η κιτικολίνη διαθέτει τόσο τα θεραπευτικά αποτελέσματα όσο και το θεμέλιο ασφαλείας που απαιτείται για καθημερινή, μακροχρόνια χρήση.

Αυτή η ερευνητική βάση είναι ο λόγος για τον οποίο η κιτικολίνη έχει κερδίσει τη θέση της στην τεκμηριωμένη γνωστική ενίσχυση. Τα οφέλη είναι πραγματικά, μετρήσιμα και διατηρήσιμα - ακριβώς αυτό που θέλετε από μια ένωση που παίρνετε για τη μακροπρόθεσμη υγεία του εγκεφάλου.

Μετά την εξέταση ερευνών δύο δεκαετιών σε χιλιάδες συμμετέχοντες, η κιτικολίνη ξεχωρίζει στο γεμάτο νοοτροπικά τοπίο για έναν κρίσιμο λόγο: διαθέτει τα δεδομένα ασφάλειας και αποτελεσματικότητας που απλά λείπουν από τα περισσότερα συμπληρώματα.

Ενώ πολλά συμπληρώματα για τον εγκέφαλο βασίζονται σε θεωρητικούς μηχανισμούς ή μικρές προκαταρκτικές μελέτες, η κιτικολίνη έχει δοκιμαστεί συστηματικά σε διάφορους πληθυσμούς - από ασθενείς με εγκεφαλικό επεισόδιο έως υγιείς ηλικιωμένους ενήλικες και άτομα με τραυματικές εγκεφαλικές κακώσεις. Η συνέπεια του προφίλ ασφαλείας της σε όλες αυτές τις μελέτες είναι πραγματικά αξιοσημείωτη. Είτε οι μελέτες δοκίμασαν 500 mg ημερησίως σε υγιείς ενήλικες είτε 2000 mg ημερησίως σε σχεδόν 2.300 ασθενείς με εγκεφαλικό επεισόδιο, το ίδιο καλοήθες προφίλ ασφάλειας προέκυψε επανειλημμένα.

Αυτή η εκτεταμένη βάση ασφάλειας είναι ο λόγος για τον οποίο η κιτικολίνη κέρδισε τη θέση της στο σκεύασμά μας. Δεν τζογάρουμε με μη αποδεδειγμένες ενώσεις ούτε κυνηγάμε την τελευταία τάση. Βασιζόμαστε σε μια σταθερή βάση αποδείξεων που καλύπτει πολλαπλές ερευνητικές ομάδες, πληθυσμούς και κλινικά πλαίσια.

Η συμπερίληψη της κιτικολίνης αντιπροσωπεύει τη δέσμευσή μας για διαμόρφωση βασισμένη σε αποδείξεις. Κάθε συστατικό πρέπει να πληροί τα ίδια πρότυπα: ισχυρά δεδομένα ασφάλειας, ουσιαστική έρευνα αποτελεσματικότητας και σαφείς μηχανισμοί δράσης. Η κιτικολίνη περνά και τις τρεις δοκιμασίες με πειστικό τρόπο.

Το πιο σημαντικό είναι ότι η συμπερίληψη της κιτικολίνης αντικατοπτρίζει την ευρύτερη φιλοσοφία μας: η γνωστική ενίσχυση πρέπει να βασίζεται σε στέρεες βάσεις, όχι σε φανταχτερές υποσχέσεις. Η πραγματική γνωστική υποστήριξη προέρχεται από την κατανόηση του τρόπου λειτουργίας του εγκεφάλου και την υποστήριξη αυτών των μηχανισμών με ενώσεις που έχουν μελετηθεί διεξοδικά. Αυτό είναι ακριβώς το είδος της βάσης που θέλουμε για τη γνωστική ενίσχυση που προορίζεται να χρησιμοποιείται καθημερινά, μακροπρόθεσμα.

Όταν επιλέγετε τι θα βάζετε στο σώμα σας κάθε μέρα, το βάθος της έρευνας πίσω από κάθε συστατικό έχει σημασία. Η κιτικολίνη έχει κερδίσει αυτή την εμπιστοσύνη μέσα από δεκαετίες συστηματικής μελέτης. Γι' αυτό είναι εδώ και γι' αυτό παραμένει.

Πνευματικά δικαιώματα 2024 © Mountaindrop. Όλα τα δικαιώματα διατηρούνται. Powered by EOSNET